Sep 5, 2019 |

The justifiable excitement around precision oncology has to be tempered with the harsh reality that morbidity and mortality from this devastating disease remain unacceptably high, with far too few patients yet able to benefit from targeted therapy. That’s not surprising when you consider that a typical adult has 1014 cells. As our cells divide (and our DNA replicates), there are roughly 10-10 replication errors per DNA base per cell division, after proof-reading correction. Couple these facts with the 105 environmentally damaged DNA bases sustained per cell per day, and the 1015 cell divisions during a person’s lifetime, and we arrive at the astounding statistic that there are greater than 1000 somatic mutations in EVERY CELL.

Precision oncology is generally defined as treating a patient’s cancer with specific, targeted therapies, directed against their unique molecular tumor profile. This profile is generally derived by tumor and germline next-generation sequencing (NGS), coupled with additional biomarkers (that indicate, for instance, the likelihood of response to immunotherapy). Targeted cancer treatments have been launched more frequently than ever before, and an unprecedented amount of clinical development of new treatments is underway. But when you consider the staggering 1000 mutations in every cell statistic, it’s not surprising that Precision Medicine, to this point in time, is only so precise.

While current science is far from providing a uniform cure for cancer, we believe that the reasons for the lack of benefit are many-fold, and that we can do better, and that HL7 FHIR, coupled with clinical decision support (CDS) can help.

How do we overcome the barriers to precision oncology? We are far far far from understanding the complex biology of cancer. Available targeted treatment options are impressive achievements, but are woefully limited. FHIR won’t help here – rather, the incremental advancement of science will push forward, thanks to the ongoing contributions of countless basic science and clinical researchers.

But what about the knowledge we do have? What about ensuring that the right knowledge, based on a person’s unique molecular profile, can be surfaced to the right clinician at the right time at the right point of care? FHIR and CDS can definitely help here, particularly if we take a little time to better understand the barriers.

Precision treatment can be thought of as aligning available treatments (including clinical trials) with a person’s unique molecular profile. Challenging this alignment is the onslaught of genomic data generated from tumor and germline sequencing, coupled with the rapid pace of new treatment and knowledge development – this is far too much information for a clinician to manage manually. Likewise, today’s EHRs are challenged to deal with vast quantities of genomic data. And, while there are a growing number of publicly accessible oncology knowledgebases, each knowledgebase has its own mode of access, and its own scope of knowledge, such that multiple sources of information generally need to be brought to bear in order to determine the best treatment for a given individual.

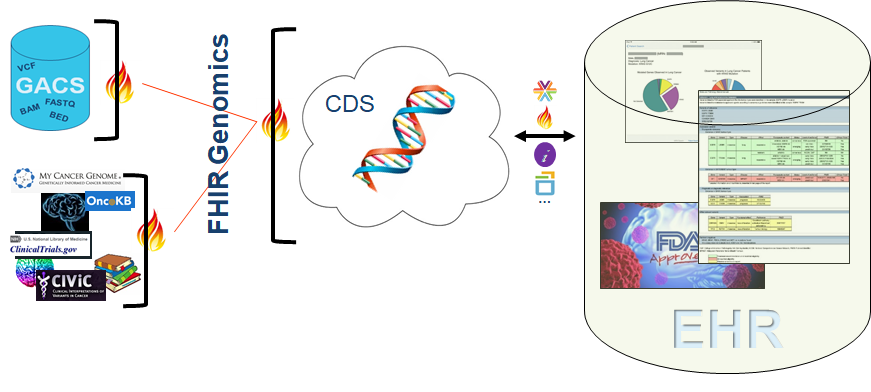

Advances in tumor sequencing are furthering our ability to discern various types of somatic variants from NGS data. Solutions such as a FHIR-enabled genomic data server (or Genomic Archiving and Communication System, GACS) that we’ve talked about repeatedly, are poised to house a person’s complete germline and somatic sequencing data and enable select portions to be served up, in real time, to clinical applications such as a CDS system. And of course, interoperability standards are driving forward, including standards for the representation of raw NGS data, standards for the representation of clinical genomic and oncology data, and standards for communicating with knowledge sources.

At Elimu, and undoubtedly at countless other institutions focused on provision of precision oncology, we envision an ecosystem as illustrated in the following picture. This ecosystem is driven by a handful of relatively simple FHIR interfaces, where disparate data sources (genomic data housed in GACS, knowledge housed in various knowledge sources, clinical data housed in an EHR) can be pulled together and intersected to create precision reports targeted to a patient’s unique molecular profile and of value to clinicians at the point of care. The premise of this model is that, without too much work, we can do better by at least making sure that what we do know is brought to bear, to oncologists, to molecular pathologists, to pharmacists, to other members of a patient’s care team, at the point of care.

We have found that precision oncology is not only viable, but that it is achievable using tools and standards currently or soon to be available. A FHIR Genomics ecosystem allows for the delivery of contextual point of care recommendations that intersect a person’s unique germline and somatic findings with various sources of knowledge. While this is far from a cure for cancer, it is an imminently tractable solution that helps ensure that what we do know is available at the point of care.